‘No other example is known of a continuous series of timber bridges occupying an important Victorian crossing since the early 1850s‘ Don Chambers ‘Wooden Wonders’

-

- At a recent Council Meeting one of Mount Alexander Shire’s councillors indicated that Sheriff’s Bridge has been noted for future works. Given the history at Froomes Road Bridge, there is reason to be concerned.

-

- Sheriff’s Bridge is a major component of the Gold Commissioner’s Camp precinct. It is protected by the HO668 ‘Camp Reserve and Environs’ local overlay. It is not, at present, listed on the VHR.

-

- Below is a history of the bridge, and an explanation of its construction and significance.

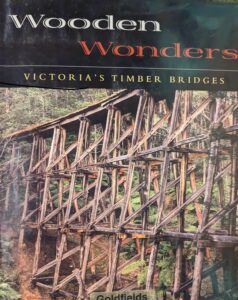

Wooden Wonders Victoria’s Timber Bridges

Author Don Chambers

Hyland House Publishing for the National Trust of Australia, 2006. pages 77-81 Extract pertaining to Sheriff’s Bridge.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

‘Although Bendigo and Ballarat would ultimately overshadow Castlemaine’s fame, the Mt Alexander gold rushes were an extremely significant part of those earliest frenetic searches for alluvial gold that made the colony of Victoria world famous. Early timber bridges of Bendigo, Ballarat and Castlemaine were largely replaced by composite constructions of masonry, iron and timber during the heyday of those mining centres, when the exceptional floods of 1870 and 1889 swept away timber bridges. The nineteenth-century history of Victorian goldfields bridge evolution largely revolves around those destructive floods, whose nasty consequences were greatly aggravated by an incredible amount of mining sludge from indiscriminate alluvial mining, with its ‘paddocked’ deep loose earth, its sluices and its puddling machines, and the fouling of waterways mine tailings.

What would the first timber bridges built on the Mt Alexander goldfields have looked like? Rough constructions of tree trunks and saplings or split slabs were initially thrown over troublesome streams, to be swept away by the first big rains. The first government-built bridge on the Mt Alexander diggings was the timber structure over Campbells Creek near the Sheriff’s quarters at the Government Camp; a key crossing place on the main road linking the Ballarat and Bendigo diggings. It was a very narrow all-timber bridge, just wide enough to cater for one laden bullock dray. We do not know whether its timber beams were square-hewn or simply round logs. Public Works Department plans of the early 1860s indicate both square and round beam designs. Being situated on a rough goldfields site, it is likely forest logs were used.

As a ‘superior’ government-built bridge, the first Sheriff’s Bridge probably featured timber-pile abutments with hewn-timber sheeting. That early bridge almost certainly had transverse or cross decking, fixed directly to beams or stringers. In short, the timber construction of the original bridge probably had much in common with the basic structure of the broader seven-span timber bridge that crosses Campbells Creek today. The site that knew Castlemaine’s first official timber bridge today boasts that town’s last substantial timber road bridge. In very few old gold towns can one find a crossing where a timber bridge has existed continuously since the early 1850s.

In 1860, a new government bridge was built over Forest Creek at the end of Barker St, Castlemaine. The bustling Government Camp with its Goldfields Commissioner and its Sheriff resident near the original crossing soon passed into history; leaving ‘Sheriff’s Bridge’ sitting in a quiet backwater. Probably because it was so early displaced from its official main-road status, it continued to function as an all-timber bridge long after its neighbours were replaced by composite structures.

Sheriff’s Bridge was first seriously battered by floods in 1856, and Archibald Oughton was contracted by Melbourne’s Central Road Board in 1857 ‘to execute repairs.[1] Complaints continued. Apart from innumerable drays and wagons, there were in 1859 ‘three daily stages to Ballarat, and twelve or fifteen conveyances running to Fryers Town, Guildford, Pennyweight, Kangaroo and the Five Flags (Campbells Creek). At present two vehicles can hardly pass one another on the Sheriff’s Bridge, without dangers of collision, and one bullock team completely blocks up the roadway.’[2] Late in 1859, only months before the next big flood struck, reporters claimed that ‘portions of the rail and parapet have tumbled into the creek, and the rest will follow suit before long’. Mining sludge was already choking Campbells Creek almost to road level.[3]

Early in April 1860, Sheriff’s Bridge was hit by a second deluge. Muckleford Bridge ‘fell in’ and nearby Winter’s Flat became ‘a huge lake’, but the pile-pier substructure of Sheriff’s Bridge apparently survived.[4] In early May it was reported that ‘the Sheriff’s Bridge is every now and then being blocked up by the traffic, and since the rails have been thrown down this crossing is more than ever inconvenient and unsafe.[5] In the following month something was being done about its safety. Few districts were then fortunate enough to possess a government bridge, and Castlemaine was in a better position than most to obtain government funding.

When the next major flood hit Sheriff’s Bridge in 1870, it was no longer the main vehicle crossing between Ballarat and Bendigo via Castlemaine. The whole of Campbells Creek Road (present Midland Highway) was under water in October 1870 and ‘only the vestiges – and they are but a few piles – of the old Sheriff’s Bridge could be seen’.[6] Castlemaine Council was confronted with the task of replacing a whole series of bridges.

A few important main-road bridges, which drew substantial state government flood subsidies, would be replaced using stone masonry, and wrought-iron beams supporting timber decks and sides. However, surviving plans for a replacement structure at the Sheriff’s crossing indicate an all-timber bridge constructed mainly of sawn red gum timber, apart from squared stringers that were to be of grey box, or ironbark. [7] That is, the original rough pioneering timber structure was replaced by a more fashionable timber bridge constructed according to traditional British tenets of bridge carpentry but utilizing superior Australian hardwood timbers.

Sheriff’s Bridge needed to be strong, because in the New Year of 1889 it would be hit by the most devastating flash flood to come down Campbells Creek. By way of graphic illustration, the 1889 flood swept away the British Queen Head Hotel at Vaughan, with its inhabitants, down the Loddon River. When that flood subsided, it was claimed that the old Vaughan hotel site was covered by silt and mine debris to a depth of 18 feet (approximately 5.5 metres).

Castlemaine’s reconstructed timber bridges were mostly wrecked, while isolated masonry and timber or masonry and wrought-iron structures built after the 1870 floods stood firm, with debris from demolished timber bridges piled against them. The message was quickly received that more masonry and wrought-iron bridges were in order. But timber was generally used for decks and railings. An artist’s impression of the 1889 devastation in the vicinity of the Castlemaine Camp Reserve indicates a battered but largely intact all-timber Sheriff’s Bridge standing disconsolately in the middle foreground of a watery wasteland.

The red gum timber superstructure of the post 1870 bridge, not helped by its total immersion and flood battering in 1889, would have needed major renovations by early last century. By the end of World War II, the old timber-pile piers of 1871-72 would have approached the end of their useful life. The current timber substructure of Sheriff’s Bridge, still possessing seven spans like the post-1870 bridge, most probably dates form the period of post-war reconstruction.

More recent still is a cleverly designed superstructure, combining colonial Australian timber-bridge features with some unusual up-to-date engineering to protect its hardwood frame from dangerous moisture penetration. Despite many changes since the gold era, the current bridge retains enough traditional timber-bridge styling for it to qualify as the continuance of one of Victoria’s most historic stream crossings. No other example is known of a continuous series of timber bridges occupying an important Victorian crossing since the early 1850s; most main-road crossings of that era are now bridged by concrete.’

[1] Victorian Government Gazette, 1857, vol 2, p.1374.

[2] Mt Alexander Mail, 19 Jan 1859.

[3] Ibid;18 Dec. 1859, 30 March 1859.

[4] Ibid; 6 April 1860.

[5] Ibid;2 May 1860.

[6] Public Record Office, Laverton VPRS 1115, Unit 1, p. 116, letter dated 13 June 1860.

[7] The Castlemaine Representative, 7 October 1870.

To support the Sheriff's Bridge

Financially support an expert Victorian Heritage Register nomination

Contact the Castlemaine Society Inc

castlemaine society@gmail.com

Contact your local Council member

Protect Goldfields Heritage